Orientation: “FACILE Pharmacology” will eventually be published as a book or as a section of an upcoming new edition (eg of Inflammation Mastery); as each section is finished, I will post the text (public, within limits) and PDF (for paid subscribers) along with video narrations.

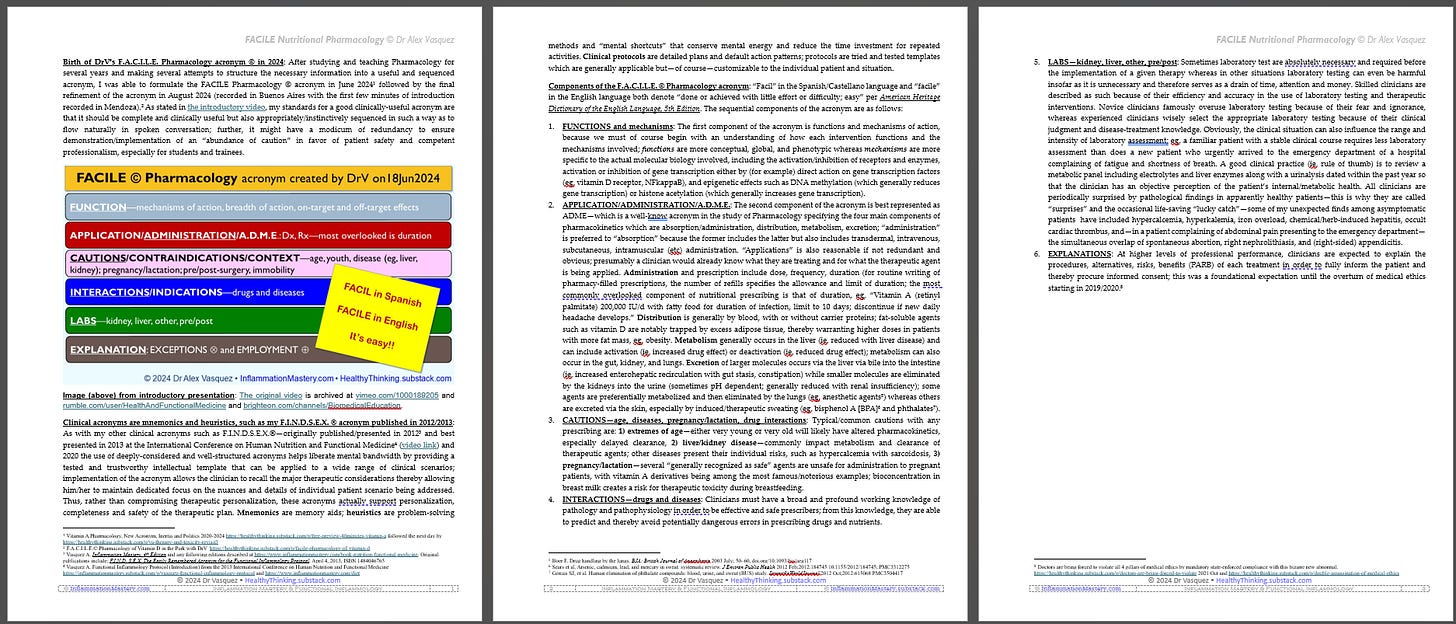

Birth of DrV’s F.A.C.I.L.E. Pharmacology acronym © in 2024: After studying and teaching Pharmacology for several years and making several attempts to structure the necessary information into a useful and sequenced acronym, I was able to formulate the FACILE Pharmacology © acronym in June 2024[1] followed by the final refinement of the acronym in August 2024 (recorded in Buenos Aires with the first few minutes of introduction recorded in Mendoza).[2] As stated in the introductory video, my standards for a good clinically-useful acronym are that it should be complete and clinically useful but also appropriately/instinctively sequenced in such a way as to flow naturally in spoken conversation; further, it might have a modicum of redundancy to ensure demonstration/implementation of an “abundance of caution” in favor of patient safety and competent professionalism, especially for students and trainees.

Image (above) from introductory presentation: The original video is archived at vimeo.com/1000189205 and rumble.com/user/HealthAndFunctionalMedicine and brighteon.com/channels/BiomedicalEducation.

Clinical acronyms are mnemonics and heuristics, such as my F.I.N.D.S.E.X. ® acronym published in 2012/2013: As with my other clinical acronyms such as F.I.N.D.S.E.X.®—originally published/presented in 2012[3] and best presented in 2013 at the International Conference on Human Nutrition and Functional Medicine[4] (video link) and 2020 the use of deeply-considered and well-structured acronyms helps liberate mental bandwidth by providing a tested and trustworthy intellectual template that can be applied to a wide range of clinical scenarios; implementation of the acronym allows the clinician to recall the major therapeutic considerations thereby allowing him/her to maintain dedicated focus on the nuances and details of individual patient scenario being addressed. Thus, rather than compromising therapeutic personalization, these acronyms actually support personalization, completeness and safety of the therapeutic plan. Mnemonics are memory aids; heuristics are problem-solving methods and “mental shortcuts” that conserve mental energy and reduce the time investment for repeated activities. Clinical protocols are detailed plans and default action patterns; protocols are tried and tested templates which are generally applicable but—of course—customizable to the individual patient and situation.

Components of the F.A.C.I.L.E. © Pharmacology acronym: “Facil” in the Spanish/Castellano language and “facile” in the English language both denote “done or achieved with little effort or difficulty; easy” per American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition. The sequential components of the acronym are as follows:

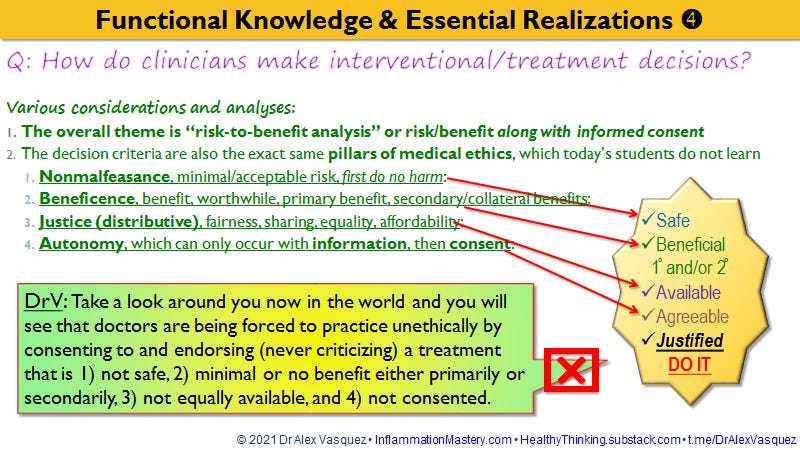

1. FUNCTIONS and mechanisms: The first component of the acronym is functions and mechanisms of action, because we must of course begin with an understanding of how each intervention functions and the mechanisms involved; functions are more conceptual, global, and phenotypic whereas mechanisms are more specific to the actual molecular biology involved, including the activation/inhibition of receptors and enzymes, activation or inhibition of gene transcription either by (for example) direct action on gene transcription factors (eg, vitamin D receptor, NFkappaB), and epigenetic effects such as DNA methylation (which generally reduces gene transcription) or histone acetylation (which generally increases gene transcription).

2. APPLICATION/ADMINISTRATION/A.D.M.E.: The second component of the acronym is best represented as ADME—which is a well-know acronym in the study of Pharmacology specifying the four main components of pharmacokinetics which are absorption/administration, distribution, metabolism, excretion; “administration” is preferred to “absorption” because the former includes the latter but also includes transdermal, intravenous, subcutaneous, intramuscular (etc) administration. “Applications” is also reasonable if not redundant and obvious; presumably a clinician would already know what they are treating and for what the therapeutic agent is being applied. Administration and prescription include dose, frequency, duration (for routine writing of pharmacy-filled prescriptions, the number of refills specifies the allowance and limit of duration; the most commonly overlooked component of nutritional prescribing is that of duration, eg, “Vitamin A (retinyl palmitate) 200,000 IU/d with fatty food for duration of infection, limit to 10 days; discontinue if new daily headache develops.” Distribution is generally by blood, with or without carrier proteins; fat-soluble agents such as vitamin D are notably trapped by excess adipose tissue, thereby warranting higher doses in patients with more fat mass, eg, obesity. Metabolism generally occurs in the liver (ie, reduced with liver disease) and can include activation (ie, increased drug effect) or deactivation (ie, reduced drug effect); metabolism can also occur in the gut, kidney, and lungs. Excretion of larger molecules occurs via the liver via bile into the intestine (ie, increased enterohepatic recirculation with gut stasis, constipation) while smaller molecules are eliminated by the kidneys into the urine (sometimes pH dependent; generally reduced with renal insufficiency); some agents are preferentially metabolized and then eliminated by the lungs (eg, anesthetic agents[5]) whereas others are excreted via the skin, especially by induced/therapeutic sweating (eg, bisphenol A [BPA][6] and phthalates[7]).

3. CAUTIONS—age, diseases, pregnancy/lactation, drug interactions: Typical/common cautions with any prescribing are: 1) extremes of age—either very young or very old will likely have altered pharmacokinetics, especially delayed clearance, 2) liver/kidney disease—commonly impact metabolism and clearance of therapeutic agents; other diseases present their individual risks, such as hypercalcemia with sarcoidosis, 3) pregnancy/lactation—several “generally recognized as safe” agents are unsafe for administration to pregnant patients, with vitamin A derivatives being among the most famous/notorious examples; bioconcentration in breast milk creates a risk for therapeutic toxicity during breastfeeding.

4. INTERACTIONS—drugs and diseases: Clinicians must have a broad and profound working knowledge of pathology and pathophysiology in order to be effective and safe prescribers; from this knowledge, they are able to predict and thereby avoid potentially dangerous errors in prescribing drugs and nutrients.

5. LABS—kidney, liver, other, pre/post: Sometimes laboratory test are absolutely necessary and required before the implementation of a given therapy whereas in other situations laboratory testing can even be harmful insofar as it is unnecessary and therefore serves as a drain of time, attention and money. Skilled clinicians are described as such because of their efficiency and accuracy in the use of laboratory testing and therapeutic interventions. Novice clinicians famously overuse laboratory testing because of their fear and ignorance, whereas experienced clinicians wisely select the appropriate laboratory testing because of their clinical judgment and disease-treatment knowledge. Obviously, the clinical situation can also influence the range and intensity of laboratory assessment; eg, a familiar patient with a stable clinical course requires less laboratory assessment than does a new patient who urgently arrived to the emergency department of a hospital complaining of fatigue and shortness of breath. A good clinical practice (ie, rule of thumb) is to review a metabolic panel including electrolytes and liver enzymes along with a urinalysis dated within the past year so that the clinician has an objective perception of the patient’s internal/metabolic health. All clinicians are periodically surprised by pathological findings in apparently healthy patients—this is why they are called “surprises” and the occasional life-saving “lucky catch”—some of my unexpected finds among asymptomatic patients have included hypercalcemia, hyperkalemia, iron overload, chemical/herb-induced hepatitis, occult cardiac thrombus, and—in a patient complaining of abdominal pain presenting to the emergency department—the simultaneous overlap of spontaneous abortion, right nephrolithiasis, and (right-sided) appendicitis.

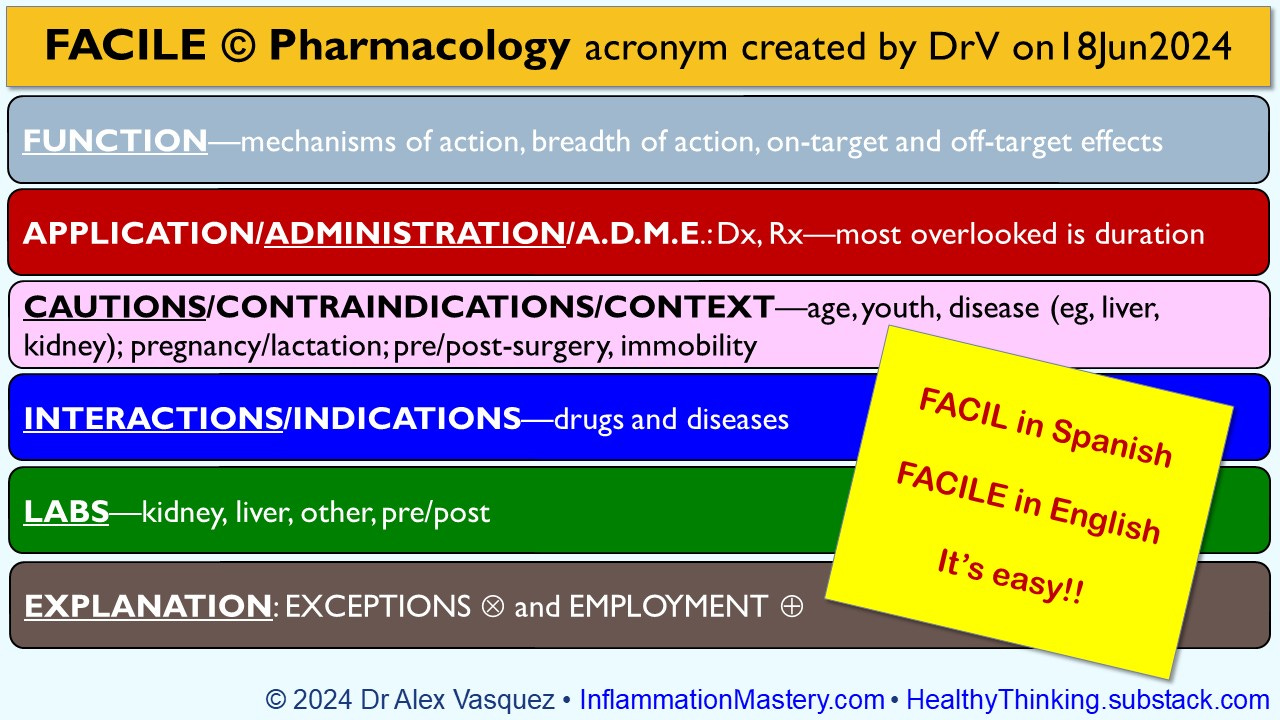

EXPLANATIONS: At higher levels of professional performance, clinicians are expected to explain the procedures, alternatives, risks, benefits (PARB) of each treatment in order to fully inform the patient and thereby procure informed consent; this was a foundational expectation until the overturn of medical ethics starting in 2019/2020.[8]

Doctors are being forced to violate all 4 pillars of medical ethics by mandatory state-enforced compliance with this bizarre new abnormal

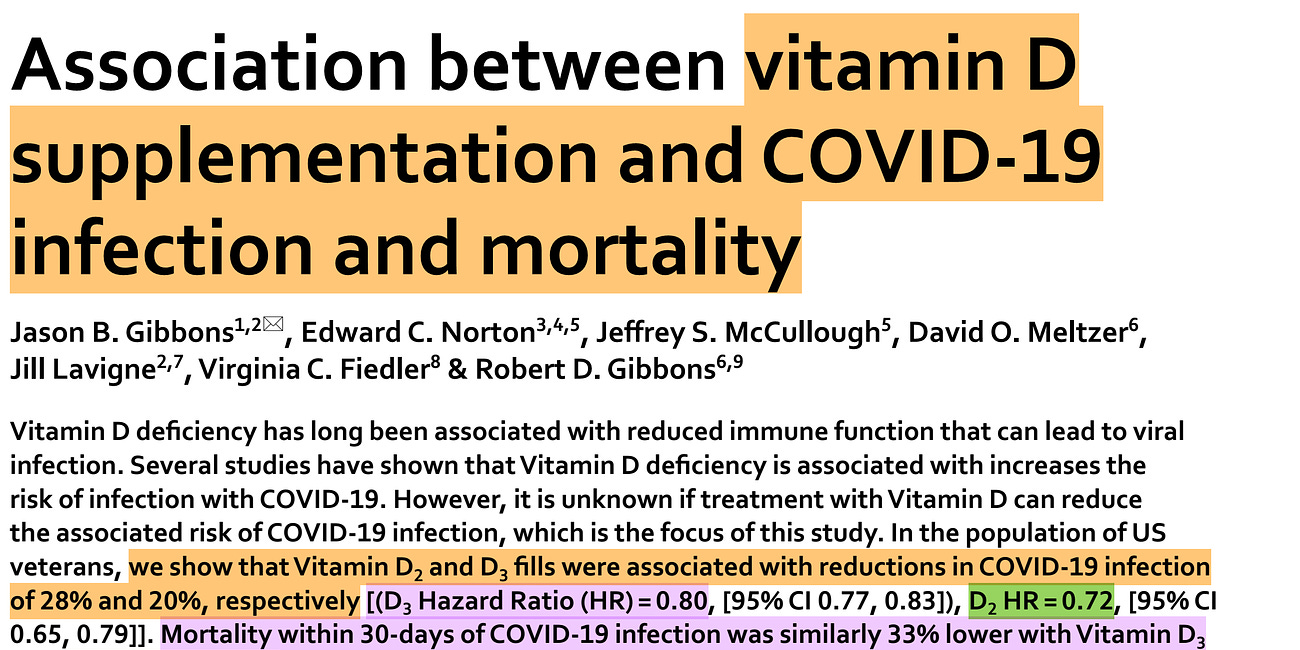

I am currently working on Video no5 in my series on ReDefining Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults which will focus on Immune Defense against Infectious Diseases; see topical listing provided below for other videos on the theme of vitamin D.

New research finds that 116,000 American deaths and 4 million COVID-19 cases could have been avoided with low-cost low-risk multiple-benefit vitamin D supplementation, especially at 50,000 units daily

A new study published in the open-access peer-reviewed journal Scientific Reports (2022 November*) shows us anew what we have already known: